30/03/2018

Blog technique

BADFLICK is not so bad!

Florent Saudel

We present here an in-depth analysis of the BADFLICK backdoor, which is used by the TEMP.Periscope group also known as « Leviathan ».

Overview

Recently the malware analysts from FireEye [1] detected a re-emerging threat targeting maritime and engineering industries. Moreover, they made a connection between this campaign and a group which they tracked since 2013 and which is also known as « Leviathan » [2] by the researchers of the ProofPoint security firm.

Description of the BADFLICK malware

The BADFLICK malware, as described in the FireEye’s blog post seems to be a new backdoor. Besides, we have not found a detailed description of the BADFLICK’s inner mechanisms, so we propose to do it here in this blog post.

In-depth analysis of the BADFLICK backdoor

Overview

BADFLICK is a PE32 executable and no trace of any kind of obfuscation or anti-debug technique is present.

Also, the backdoor does not try to be persistent in any way. As its behaviour suggests, BADFLICK is just a temporary reverse shell, downloader and launcher for a potentially more advanced backdoors or exploits.

An inoffensive threat

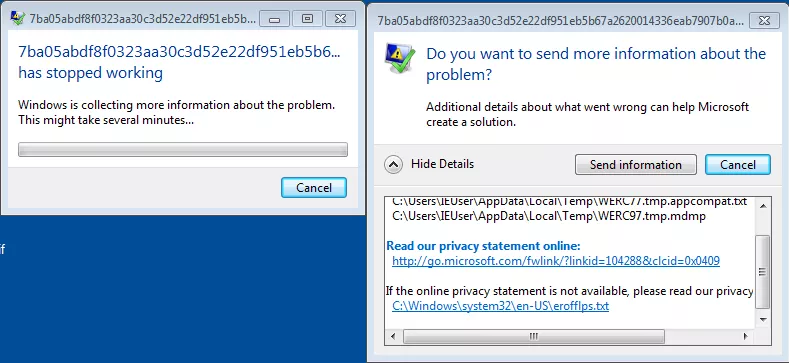

Surprisingly, the historical BADFLICK sample referenced in the FireEye blogpost (bd9e4c82bf12c4e7a58221fc52fed705) is bugged and it crashes during an aPLib compression routine.

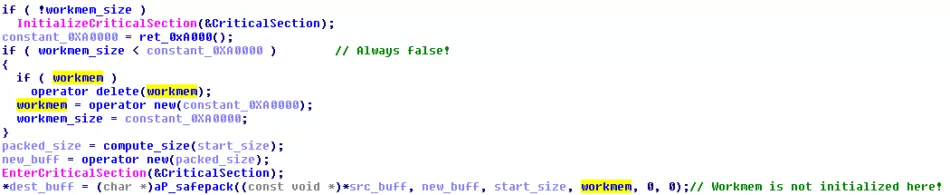

The aPsafe_pack function of the library needs a working buffer allocated by the caller. BADFLICK allocates one global buffer, whose size is defined by a global variable. Besides, this buffer can grow when needed.

However on the sample given by FireEye, the global size is already set to the 0xA0000, but the buffer is not allocated. Thus, the code considers the buffer as already allocated and gives a wrong pointer to the aPsafe_pack function.

To proceed further our investigation, we patched these two global variables, setting them to zero to trigger the initial allocation. We also patched the malware’s configuration IP address to redirect its traffic to our own local fake Command and Control (CC) server.

Description of BADFLICK's behaviour

BADFLICK’s behaviour is driven by a configuration string hard-coded in the data section of the malware: "1|103.243.175.181|80|5|xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx".

Each option is separated by a « | » character. This string can be interpreted as:

- 1: this number represents the current state of the backdoor. The statical analysis let us guess three different possible states (see below) ;

- 103.243.175.181: IP address of the CC server ;

- 80: the TCP port ;

- 5: the number of minutes to wait between two connections.

Regarding the 103.243.175.181 server, it resolved to the « update.wsmcoff.com » domain at the beginning of 2018. « wsmcoff.com » extends other subdomains such as « api.wsmcoff.com », « kc.wsmcoff.com », « info.wsmcoff.com » or « store.wsmcoff.com », which all seem quite malicious regarding their quite generic names. « update.wsmcoff.com » now resolves to 185.174.173.157.

Default startup routine

Once its configuration is parsed, BADFLICK starts sending some information about the victim computer to its CC server. This information contains: – the computer name; – its IP address; – statistics about the CPU, the total size of the memory, etc.; – constant string "winMain static green".

BADFLICK uses a custom TCP-based protocol where data is compressed. Copyright strings in the binary tell us that the aPLib library is embedded in BADFLICK’s code and potentially used for this purpose.

Description of the network protocol

This protocol is composed of three nested layers:

Layer 1

The first layer starts with a header composed of nine bytes followed by an aPLib archive:

- the first DWORD of the header is the archive’s size;

- the next DWORD is a dynamic value computed by BADFLICK, wich equals to 0x2C0134FE minus the aPLib archive size and it is used later to unpack the next layer;

- the 9th byte is used as a boolean to show if the data that follows is compressed or not.

Our tests and our analysis of the code seems to show that all the data sent by BADFLICK is compressed and thus this 9th byte always equals to 0x1.

em ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Layer 2

The second layer, which starts at the offset 9, is a compressed aPLib archive with its magic string « AP32 » altered.

To restore this archive and unpack it, BADFLICK computes a XOR between the first DWORD and the dynamic magic value stored in the layer 1. The result is therefore always 0x32335041 which is « AP32 » in ASCII.

At this point, the layer 2 is a valid aPLib archive. It starts with an header composed of six DWORDs:

- « AP32 » magic value ;

- header size (24);

- compressed data size;

- compressed data CRC32;

- uncompressed data size;

- uncompressed data CRC32.

In succession, there is the packed data.

The point of the alteration of the aPLib archive magic is to hide it because it would be a good fit for a network signature. However, our tests showed that the system information collected and send by BADFLICK are almost always smaller than 256 bytes. Therefore, even if the « AP32 » magic string is altered with a value which depends on the size of the data sent, the three higher bytes of the dynamic value are always the same: 34 01 2c.

Furthermore, it also completely forgets to hide the header size of the aPLib compressed buffer which is the constant 24, and the higher bytes of the compressed data size.

We can leverage the particularities of BADFLICK’s network protocol to produce a snort rule to detect the exchanges between BADFLICK and its CC presented at the end of this blog post.

To obtain the last layer which is the uncompressed data, BADFLICK uses the aP_depack_safe function of the aPLib library.

Layer 3

Once uncompressed, the last layer also starts with a header of five bytes followed by the data: – the first byte in the header represents the type of request sent; – the last 4 bytes are a DWORD value which is the data size.

Finally, the data is copied in succession.

BADFLICK's capabilities

BADFLICK’s code is clear enough to guess the next operations when BADFLICK success to reach it.

When the connection is established, the backdoor creates a new thread waiting for the commands coming from the CC. In this loop, BADFLICK accepts three different commands. The first byte (printable) in the layer 1 packet defines their types:

- « / » means that BADFLICK will send its current configuration to the CC;

- « 3 » sets up a reverse shell;

- « 8 » forces BADFLICK to create another thread that implements seven new commands related to file system manipulation.

The « 8 » commands are:

- « : »: listing drives;

- « > »: upload files to the CC server;

- « @ »: download files;

- « K »: search files;

- « L »: create directory;

- « M »: delete a file or directory;

- « N »: move a file.

Alternative configurations

The BADFLICK’s code shows an alternative configuration mode different from « 1 », which enables a « stealthier » version of the backdor.

This configuration expects four arguments passed on the command line.

If only three parameters are passed on the command line, BADFLICK uses a well-known process hollowing technique, similar to the « MockDLL » tool used by the « Leviathan » group.

The purpose of MockDLL is to hide the execution of a process by changing its name. To do so, MockDll creates a mock process (defaulting to a regsvr32 instance) and then unmaps its address space to replace it with the code and data of another hidden executable.

BADFLICK reuses this same principle to launch a new instance of itself with five arguments in a regsvr32 instance. The first three parameters are the backdoor configuration (ip address, port number and time to wait between two connections). The fourth argument is the string « go » and the last argument is the path of the BADFLICK binary.

Therefore, the four arguments configuration is just the launcher stage for the « stealthier » variant of the backdoor.

When five arguments are passed on the command line, BADFLICK will also initialise a communication with the CC server. However, the string sent to the server is modified. The last line "winMain static green" is replaced by another message "[Green] pid=%d tid=%d modulePath=%s|" which contains also the current process id, thread id and module name of the backdoor.

Besides, BADFLICK takes two additional precautions before contacting the CC: 1. It checks that the fourth parameters is indeed the string « go ». 2. It deletes the files specified by the last parameter. Hence, BADFLICK removes itself from the file system of the victim.

Besides process hollowing artifacts (process with its main module memory section not backed to an existing file/to its regular file), a running process with a « go » commandline argument folowed by a path might be a good system IOC.

Conclusion

It is not clear why this malware sample has gone public, as a simple test would have made clear that it cannot run and may trigger some alerts when crashing. However, it remains quite simple to detect, either from memory or the network, and we believe it is only used as a first stage malware to recon and drop other and more advanced ones. We actually believe the « wsmcoff.com » subdomains are malicious and that outgoing connections to them should trigger alarms.

Snort rule

alert tcp $HOME_NET any -> $EXTERNAL_NET any (msg:"BADFLICK First Packet"; content: "|00 00 00|"; offset: 1; content: "|34 01 2c 01|"; offset: 5; content: "|64 32 1e 18 00 00 00|"; offset: 10; sid:1;)